- Home

- Michael Thomas Ford

Lily Page 3

Lily Read online

Page 3

It was nearing midnight, and the villagers were gathering in the center of the Hall to dance. The frenetic movement of hands and feet, they knew, kept away anything that might wish them harm. The rush of bodies moving about the room was sure to create a circle of love and warmth into which nothing dark could pass. And in movement and dance and laughter, they were reminded that they were alive, that their arms and legs could still respond to the sounds of fiddle, flute, and bells.

Joining the others, Lily stood in a ring of women, forming a large circle around the center of the Hall. The men stood outside them, also in a ring, their faces bright with smiles as they stamped their feet and prepared to begin. In the corners, children laughed and giggled as they made their own small circles in imitation of their elders.

Picking up his fiddle, Arnson Pimball sounded the rush of light notes that signaled the start of the dance. When Kaylie Featherfew joined in with her flute, the women bent their knees and began a slow walk to the right, their hands clapping a beat. The men moved in the opposite direction, circling widdershins while their heavy boots made sounds like drums.

Lily watched the faces of the men pass by her as she moved in place between Anne Cooper and old Tressa McSnare. Each one was familiar to her, but she found herself mesmerized as she studied the lines and shadows of eyes and mouths, searching for something that would recall her father’s face. As each man passed her, she paused a moment before looking at the next, as though in the time between her father would rise from the dead and come to take his place in the dance, as he had many times before.

When the circles had passed one another and each man had seen each woman’s face, the music began to quicken. Kaylie’s flute ran like a brook beneath the notes twirling from Arnson Pimball’s fiddle, and the dancers prepared to begin the chain in which each woman grasped the hand of the man across from her and the circles intertwined, with each woman spinning around each man and moving on to the next. Stopped across from her childhood friend Peter Layman, Lily reached out and took his hand in hers.

Immediately, she was struck by a vision of Peter as an old man, his children, yet to be born, gathered around him as he lay dead upon his bed. The image was a peaceful one, and Lily sensed nothing but love in it, but its impact was as if someone had struck her in the head with a rock. It overwhelmed everything else, and she could feel every emotion as though it were her own. She knew the confusion felt by Peter’s youngest daughter as she looked into her father’s face. She sensed the separation that was just beginning to soak into the heart of his widow as she gazed into the future and saw herself alone. All of these things exploded into her mind in a single instant, battering her with sensations.

Before she had time to recover, she was passed to the next waiting hand, belonging to Hugh Van Woojin, whose cows provided the village with milk and cheese. As his calloused fingers closed around hers, the vision of Peter’s death was swept from her head and replaced with one of Hugh, his face contorted in agony, stretched in the field while his cows looked down at him with puzzled expressions on their placid brown faces. Lily felt the crazy jump of Hugh’s heart as it beat out of time and pain shot through his chest. She saw clearly the heavy stone he had just attempted to lift, and felt the rawness of his skin where it had fallen from his hands as he’d stumbled under its weight. Then his eyes opened, taking in the familiar faces of his herd and the sun flashing above them, and he died.

Again Lily felt herself passed to another hand, and again a vision came. A vision of death. She closed her eyes tightly and tried to concentrate on the music. She attempted to grasp onto the notes that tumbled from Arnson Pimball’s fingers and ride them, letting them lift her above the pictures that flashed across the wall of her skull like the ever-shifting images of a kaleidoscope. But time and again she was jolted away from the music as first one scene and then another played itself out in the moments during which she touched the hands of the people she’d known all her life. She saw how each would die, most peacefully, but some in great pain.

The dance became faster, and Lily felt as though she were being twirled in seven directions at once as her body spun and swayed, kept afloat by hands that, while holding her up, were also the cause of constant terror. Her blood shrieked in her veins, and she felt her skin grow overheated until she was sure she would burst into flame. Through the haze of her visions, she saw their faces, laughing and gay, dodging in and out of sight. What must she look like to them? Did a bright smile cover the dizzying fall she was taking inside of herself? She wanted to scream for them to stop, but as when she saw her father’s death, her throat was locked. All she could do was surrender herself to the movement around her and hope that it would end before she was torn apart.

Tableau after tableau bloomed and died in her mind while the music played on. She saw Gudrun Caster felled by a sliver of lightning, and Arles Hewer taken by the vengeful shade of his brother, Shane Egan choking on the bone of a haddock and Molly Pillsin leaping from the cliffs afterwards with their child still in her belly. She saw women and men in their beds, dead while sleeping, their eyes closed as if in dreams. She saw hanged men and women killed by poisons. She saw a woman trampled by a horse and a man whisked into the darkness as the Fair Folk lifted him out of his boat. Most painful for her were the drownings, the faces floating up blue and lifeless as her father’s had. One after the other they came, and she was helpless against them.

Then the music stopped, and Lily fell to the floor. As quickly as they’d come, the visions swept out of her mind, leaving her shivering and empty. She opened her eyes, and saw that people were staring down at her, concern worrying their faces. Maxon Ashe reached down to help her up, and she twisted away. “No!” she yelled in a hoarse voice. “Don’t touch me!”

Maxon drew back, confused. Lily couldn’t tell him that only moments ago she’d seen him mauled by a bear hungry from a long winter of starvation. She only knew that if he touched her the vision would return, and that her heart would tear from any further pain. She lay on the floor and wept while around her people spoke in whispers of madness and enchantment.

Then Alex Henry’s face broke through the crowd, and he was beside her as he’d been that morning. “The visions,” she said softly. “They’ve come back.”

F O U R

BABA YAGA LEANED over the side of the mortar and looked down at the tops of the trees as she passed over them. It was night, and the moon was full, silvering everything beneath it so that the forest appeared to be a sea. The smell of fir and pine floated on the warm summer air, and owls flew alongside her, hooting curiously. All things considered, it was a lovely evening for traveling.

She had not been out of the forest in quite some time. Years, surely. A century or more, possibly. She couldn’t really remember. And why had she last left? She thought perhaps it had been to chase down that willful girl, Vasilisa. The one who had stolen her magic skull. She bristled at the memory. How the storytellers had gotten that one so wrong, she would never understand. But it was typical of them. They always cast the young and beautiful as the heroines.

Well, it hardly mattered. The girl was long dead and turned to dirt, while she was alive and flying through the summer night on an adventure. Still, she wished she had the skull back. It was a useful thing to have. She made a note to go in search of it when she returned, then promptly forgot all about it again.

She looked up at the stars. Above her, the Swan was being chased through the sky by the Fox. In a few hours the Crippled Child would make his way through the darkness, dragging the dawn behind him. She yawned and closed her eyes. She slept very little now, often going years without stretching out in her big feather bed. But the gentle rocking of the mortar made her tired, and so she made a nest of straw and feathers in the bottom of her vessel and lay down, curling into a ball so that her knees were tucked against her chin.

It was not long after that the mortar passed over Lily’s village. Baba Yaga opened one eye. She kept very still, listening to the music.

When it abruptly stopped, she commanded the mortar to descend. It landed just outside the doors of the Great Hall, and Baba Yaga climbed over the side and went to the nearest window. She pressed her face against it and peered inside.

The girl was lying on the floor, surrounded by her people. For a moment Baba Yaga thought she might be dead, and was surprised to find that this disappointed her. Then a man reached out to help the girl and the girl came to life, crying out as if she were afraid. Baba Yaga nodded. You should be afraid, she thought. This is just the beginning.

She watched for another minute or two, then turned and hobbled back to the mortar. As it rose into the sky, she heard the music begin again. Then she passed over the houses and flew out towards the sea. In the cemetery on the point, a brokenhearted bride’s ghost paused at the edge of the cliff and for the first time in three hundred years looked up in wonder before stepping off and falling to the rocks below.

F I V E

BY THE AFTERNOON of the next day, everyone in the village knew of Lily’s curse. While certainly accustomed to the workings of magic, few had seen it manifested in such a powerful way, and the result was that Lily was looked upon with a mixture of fear and awe. Those who could remember the last time such a thing had happened passed glances between themselves and remained silent, knowing as they did that speaking of such things could cause the forces that brought them into being to behave in strange and unpredictable ways. Instead they made garlands of bird bones and dried violets and hung them on their doors.

Lily herself remained in her room, staring out at the sea and trying not to look at her hands. From time to time she picked up the mirror her father had given her and gazed at her reflection. Again she saw the bones of another girl floating beneath the smooth surface of her cheeks and the curve of her lips, and she hated what she saw. She closed her eyes, willing the girl who carried such terrible power in her hands to die, leaving behind the one who knew nothing of death. But each time she opened her eyes and saw that the other girl was still there, growing stronger with each passing day.

Through it all, her mother remained in her bedroom. She, too, had heard talk of Lily’s gift. Only unlike the villagers, she was certain that she knew well its origins, and she had spent her time on her knees in prayer to a god the villagers had no use for, and in fact had never heard talk of. It was the god of her own childhood, and she found herself crying out to him to remove from Lily whatever evil had crept into her soul and corrupted her in such a hideous way as to make her every touch open up a portal to death.

Lily could hear mumbled words floating stillborn through the house. She had no idea what her mother was doing, and was thankful only that she remained in her room and left Lily to clothe herself in a new body. She knew that her father’s death had changed something between herself and her mother, that her mother blamed her for what had happened. She knew her mother feared her in the same way she herself feared the girl moving about inside her skin, but she understood also that she would get no help in her fight.

And then her mother opened the door and announced that they were leaving the village that evening. She told Lily to pack one bag and to be ready to go when dusk descended and made it possible to pass out of the village.

Lily had never left the village. Few had. And only one—her father—had ever returned. He had refused ever to speak about what he’d seen, and likewise demanded that his wife never talk of her life before coming to her new home. This she had done out of love for him, although over time it had made her bitter and afraid, and in the end she had hated him almost as much as she loved him. The village she had always feared, and now that her husband was dead and her daughter possessed of evil, she longed for escape.

Like most of the people who lived there, Lily had given little thought to what lay beyond the lands she knew. Now, faced with the thought of leaving, she found herself very afraid. She feared also the urgency she heard in her mother’s voice, and the way in which her eyes stared past Lily as though looking at something looming dark and dangerous behind her.

Still, she knew that leaving was what she had to do, not for her mother’s sake, but for her own. She needed to run from the village and from the sea, away from the pull of its tides that drowned men and called women to throw themselves into the waves. She knew it was the tides that had summoned the blood from between her legs and woken the other girl, who fought even now to claw her way through muscle and bone to lay waste to Lily’s world. Lily could feel her fingers working their way through knots of blood in search of the door that would free her forever. Perhaps, she thought, running away from the sea would make the girl drowsy and lull her into a false sleep.

She packed quickly, filling a small bag with clothes. She put into it the hand mirror and the box with the shell, and then she was ready. She went downstairs and found her mother waiting. She too had packed almost nothing, choosing to leave behind that which belonged in the place she had been taken to by her husband. She had on the dress she had worn on the evening she’d arrived in the village, and a small hat perched on her head. Everything else remained in the house, which she left quickly and without looking back.

Once or twice as they walked down the lone road away from the village Lily saw her mother look back, as though expecting someone to be following them. But Lily knew that no one would try and stop them. People came and left the village by choice, not by force, and it was understood that no one who left ever spoke of its existence to anyone else. Even if they should, it would be impossible for someone not born into the village to find his way there.

After half an hour, they came to the bridge that passed over the river that marked the village’s easternmost edge. Surrounded as it was on the west, north, and south by the sea, the bridge provided the only way in or out of the village, not that many ever crossed its wide wooden boards. Sometimes the children, filled with the flighty courage common to the very young, would dare one another to step foot on it, but none ever got more than a few feet onto its expanse before turning and running back to the safety of the rocks that sat at the entrance, where they stood with hearts beating, laughing at their own fear as they looked into the thick fog that perpetually covered the far side of the bridge, even on the finest summer day.

As Lily and her mother approached the bridge, Lily’s heart began to sing wildly in her chest. With darkness nipping at their heels, she knew that they must cross over quickly or risk doing business with whatever dark creatures wandered the borders at night. The fog swirled before her, turning over and over upon itself like a large grey cat rolling in the grass. She looked into its grizzled center and wondered where it would take her.

Her mother started forward uneasily, her footsteps unsure as she tested the bridge, perhaps half afraid it would give way beneath her shoes. But it held, and soon they were approaching the veil of fog. Lily closed her eyes and allowed her mother to pull her into it. She felt the cool wet kiss of air around her as they passed through, and the sound of their feet became duller and somehow sadder.

Then it was over. When Lily opened her eyes again, she was standing on the other side of a bridge beneath a sky dark with night and lit by the thin breath of a moon that seemed smaller than the one that hung over the village. The air was warm, and she could not smell the sea. When she turned around, she saw that the bridge she had just crossed simply made a small jump over a trickling stream before continuing on down a dusty road.

“Where are we?” she asked her mother. “Where is the village?”

Her mother hushed her. “There is no village. There never was. Now follow me.”

Her mother began walking down the road under stars, and Lily followed. She had no idea where she was or where they were going, and she wondered about the village. She wondered, too, if in crossing over the bridge she had left behind the girl she was trying to kill. She made her hands into fists, searching them for any signs of her presence, but she felt nothing but the comforting cushion of flesh plump with fat.

They w

alked in silence for half an hour. Lily listened to the sounds of crickets in the fields on either side of the road and to the wind rustling the leaves over her head. While every now and again she would see the shape of something creep out of the tall weeds and peer at her for a moment before slipping back into the dark, she sensed that she had nothing to fear from anything that lived in the woods whose trees rose up into the sky beyond the seas of grass.

Rounding a turn in the road, Lily saw ahead of them the lights of a town. They shone harshly over the fronts of houses, filling the air with a hard white glow that hurt Lily’s eyes and made her blink. As they left the fields and woods behind and made for the streets lined with cars, she felt a strong desire to turn and run. Yet the hum of the electrical lines over her head drew her deeper in with their voices, and she found herself anxious to see what lay beyond the quiet doors.

Her mother walked down the main street as though she’d been reborn. Her gaze leapt from building to building. ”It’s still the same,” she said, her voice that of a little girl seeing her first circus. “It’s just as I remember it the night we passed through.”

“Passed through?” Lily asked. “You mean when you came to the village with father?”

Her mother turned to her, her eyes dark. “I told you not to speak of the village,” she said. “If anyone asks you, we’re from Pilotsville.”

Lily nodded, afraid to say anything that might make her mother angry. She didn’t understand why the village should remain a secret any more than she understood why they were in the town, but she knew that it was important to not draw any more attention to herself than was necessary. The girl within her fed on attention, and if she was still there, waiting, Lily was determined to starve her into death.

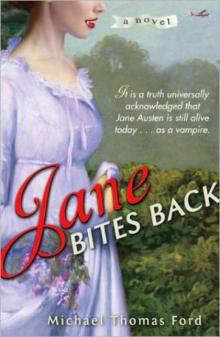

Jane Bites Back

Jane Bites Back Tangled Sheets

Tangled Sheets Z

Z Jane Goes Batty

Jane Goes Batty Lily

Lily Masters of Midnight: Erotic Tales of the Vampire

Masters of Midnight: Erotic Tales of the Vampire The Road Home

The Road Home Midnight Thirsts: Erotic Tales of the Vampire

Midnight Thirsts: Erotic Tales of the Vampire Suicide Notes

Suicide Notes Jane Goes Batty jb-2

Jane Goes Batty jb-2 Jane Vows Vengeance jb-3

Jane Vows Vengeance jb-3 Jane Fairfax 3 - Jane Vows Vengeance

Jane Fairfax 3 - Jane Vows Vengeance Michael Thomas Ford - Full Circle

Michael Thomas Ford - Full Circle Jane Bites Back jb-1

Jane Bites Back jb-1 Masters of Midnight

Masters of Midnight