- Home

- Michael Thomas Ford

Changing Tides Page 2

Changing Tides Read online

Page 2

“When are we going to get you wet?” he asked, as he always did.

“Maybe in the fall,” answered Davis, giving the answer that varied only according to whatever season followed the current one.

“One of these days you’ll say yes,” Ben said. “And I’ll drop dead of shock.”

“Well, we can’t have that,” replied Davis. “So maybe I’ll have to stay a drylander.”

After unzipping his dry suit, Ben gently pulled his hands through the latex seals that surrounded his wrists and then did the same with the seal around his neck, lifting it up and over his head to free himself. Once the suit was off, he unzipped the insulating undergarment. The sun warmed his skin, and the light breeze cooled his body, now uncomfortably warm without the cooling effects of the water.

“Got here early,” Davis remarked. “Looking for something special?”

“Just wanted to beat the crowds,” said Ben. He paused. “Actually, my daughter is coming today,” he added, surprised at himself for revealing the information.

“Daughter?” said Davis. “Since when do you have a daughter? Don’t you need a wife for that?”

Ben smiled. “Had one of those too,” he said. “It was a long time ago.”

“How old?” asked Davis. “The girl, not the wife.”

Ben thought a moment. “Sixteen,” he answered.

Davis whistled. “Good luck,” he said. “I remember when mine were sixteen. Darn near killed them. What’s she like?”

Ben sighed. “I don’t know,” he said.

Davis shot him a glance.

“It’s a long story,” said Ben. “And I don’t have time to tell it.” He put his wet gear into the large plastic tubs he carried expressly for that purpose, laid his tank alongside them, and shut the door.

“All right then,” Davis said. “Guess I’ll be seeing you later.”

“Later,” Ben said, waving briefly as he got into the car.

He backed the car out and, nodding at Davis once more, headed for the park entrance. As he went up the dirt road toward the ranger station, he wondered what had prompted him to tell the ranger about Caddie’s arrival. He’d kept her a secret for so long, why reveal her existence now?

“They had to find out sometime,” he said to himself.

He looked at the clock. It was half past eleven. Carol had said she’d be in Monterey sometime after one. That gave him just enough time to get home, clean up a little, and be ready for Caddie’s arrival.

“Who are you kidding?” he asked aloud as he passed the ranger station and headed for the highway. “You’re never going to be ready.”

CHAPTER 2

“Could you please put that window up?” Caddie looked over at her mother. “Why?”

“Because I don’t need to air-condition the entire state of California,” her mother answered. The lines around her mouth were beginning to show again, the buttresses of Botox crumbling. Soon, Caddie knew, she would go for another treatment and her face would once more be wrinkle free and expressionless.

“I like the wind,” Caddie objected.

Her mother pressed a button to raise the window. Caddie countered by pressing her own button. The window stalled; Caddie wondered if perhaps she could start a fire by keeping the machinery inside the car door fighting against itself. Then her mother would be forced to stop, to turn around, to go back.

“Why must you be so difficult?” her mother snapped, jabbing at another button with a manicured nail.

The button beneath Caddie’s finger ceased to work, its functions deadened by the override on the driver’s side. The window slid up soundlessly, sealing the car off from the outside. Immediately, Caddie felt the artificial coolness of the air-conditioning slip its chilling arms around her. She shuddered and glared at her mother.

“If the Goddess wanted us to live in bubbles, she wouldn’t have created the outdoors,” she said.

Behind her sunglasses, Carol shut her eyes momentarily and tightened her grip on the Lexus’s wheel. She felt her skin slide over the bones of her cheeks. She knew it was slipping, like snow perched on the edge of a mountain. She would have to make an appointment with Dr. Karsegian when she got back.

Caddie reached over and turned the car’s radio from the classical station Carol preferred to something raucous and nerve-jangling. Carol’s first instinct was to change it back, but she’d already won one battle with her daughter. If listening to terrible music meant an otherwise stress-free remainder of the trip, she could endure it. Maybe.

“I was supposed to go see them with Sam and Bree this weekend,” Caddie said, turning up the volume.

“See who?” asked Carol, her head beginning to throb.

“Them,” Caddie answered, nodding toward the radio. She began to sing along with the music. “ ‘I remember when you told me that you never dream in color,’ ” she warbled.

They passed a road sign—MONTEREY 25—and Carol looked at the car’s clock. They were right on time. With a little luck, she could be back in L.A. in time for dinner. As long as Ben didn’t cause any problems. But Ben always caused problems. No, she corrected herself, he didn’t cause problems, he was the problem. Ben never caused anything; he was the most passive–aggressive man she’d ever known, like a stubborn dog who pretended not to understand when you asked it to perform something as simple as sit.

“ ‘Don’t you see how blind you are?’ ” Caddie sang, loudly and badly.

For a moment, Carol thought her daughter was speaking to her. Then she saw that Caddie was looking out the window, one hand smacking forcefully against her knee. Carol noted the nails, bitten to nothing, and resisted the urge to lecture. It wasn’t her problem. Caddie wasn’t her problem. At least not for the summer.

Let Ben worry about her nails, she thought. Not that he would. Not Ben. He probably wouldn’t even notice their daughter’s nails. Carol wondered if he would even recognize Caddie if he saw her in a crowd of other teenage girls, if she wasn’t presented to him and identified, like one of his specimens.

That wasn’t fair, she told herself, at least not entirely. Ben hadn’t been the most attentive father, it was true, but he wasn’t entirely disinterested in his child. He was just, well, Ben. People as a whole didn’t particularly interest him. She didn’t know why. She’d tried to figure it out at first, when they were dating, when they were first married. She’d believed then that something terrible had happened to him to shut him off from humanity, some great trauma that, when addressed, would transform him into a loving partner.

But there was nothing. No horrible family. No childhood abuse or emotional cataclysm that might account for his behavior. Despite all of her searching, she found nothing. And so she had decided to shock him into caring with a baby. No man, she was sure, could stare into the face of his own child and not be moved to feelings of overwhelming love.

She’d even allowed him to name her, hesitating only a moment when he’d suggested Cadlina. She should have known then that she’d made a grave error in believing him capable of relating to another human being. Who, after all, named a child after a slug? But she’d allowed it, comforting herself with the fact that the obvious nickname—Caddie—was not so bad.

As if sensing her mother’s thoughts, Caddie turned toward Carol. “We could just go home,” she said. “We don’t have to keep going.”

For the first time in months, Carol agreed with her daughter. They could just go home. But, she reminded herself, home had not been a particularly enjoyable place of late. Without looking at Caddie she said, “I don’t think so.”

Reflected in the rearview mirror, she saw Caddie’s eyes darken. Then the inevitable. “I hate you.”

And I hate you, she wanted to reply. You hate me and I hate you. That makes us even. But no mother would say such a thing. Still, she felt it, and knew that countless mothers before her had felt the same thing. Perhaps one or two had even said so. But it couldn’t be true. No parent hated their child; they only hated what passed

between them. And that part was true. She did hate the dark chasm that had grown, seemingly overnight, between her and Caddie.

“He doesn’t even want me,” Caddie continued.

“He wouldn’t have asked if he didn’t,” said Carol instantly.

They both knew that was a lie. Caddie didn’t even attempt an objection. Instead, she looked out the window and remarked, “Where is this place, Iowa? It’s all farms.”

“They grow a lot of produce around here,” Carol said. “Artichokes. Strawberries.” She couldn’t think of anything else, and she knew Caddie was hardly impressed anyway. “Garlic,” she added quickly. “There’s some kind of garlic festival every year.”

“Garlic,” Caddie repeated. “That’s super. Neato.”

She pressed her forehead against the window. Outside, the green fields rolled by, seemingly without end. I’m being sent to the farm, she thought grimly. I got myself knocked up, and now I’m going to live with Aunt Bea and Uncle Henry.

If only I were knocked up, she thought. She’d know how to take care of that. But this—thing—with her mother was unfixable. It was like she’d woken up one day a different person. Maybe I’m a changeling, she told herself. Maybe the fairies will come and steal me back.

She thought of Sam and Bree back in L.A. They’d had plans. Well, sort of plans. Ideas, anyway. The details would have worked themselves out. But then her mother had dropped the bomb. “You’re going to live with your father for the summer.”

Caddie remembered with some small satisfaction her comeback. “What father?”

“There’s the ocean,” her mother said.

“Big deal,” said Caddie. “It’s the same ocean we have in L.A.”

“Three months isn’t going to kill you,” Carol said. “It might even be fun.”

Caddie looked at her. “If he’s so much fun, how come you didn’t stay married to him?” she asked.

She didn’t want an answer, and she didn’t get one. Her parents’ divorce was a closed subject. It just hadn’t worked out.

Three months. Three long months. Three long boring months. With her father. The prospect was in no way appealing. She tried to remember the last time she’d even seen her father. It had been at least a year. He’d been in L.A. for some kind of conference. They’d had dinner. He’d talked about something she didn’t understand. Squid, maybe. Or clams. He hadn’t asked her about herself at all. She’d been relieved when it was over.

Suddenly, she was overcome with a kind of panic at the prospect of living for three months with a man who spoke of nothing but clams. Turning to her mother, she said softly, “Please don’t make me go.”

For a moment, the hardness that surrounded her mother like a shell softened. Just for a moment, Caddie thought that she would acquiesce, swing the car around, and speed back to Los Angeles, where all would be forgiven. And then it passed, just as quickly, and Caddie knew she would not beg again.

Instead, she turned once more to the window. She told herself that it was a television screen, the images passing by nothing more than some program that could be changed at will, turned to some other, more interesting show. The blank shoreline, the soundless sea, the sky so flat and blue and soulless, all of them could be made to disappear with the press of a button, replaced by laughing voices and excitement, the thrill of nighttime in Los Angeles and the joy of being with Sam and Bree, who understood her without asking and didn’t make her feel somehow broken and a disappointment.

She closed her eyes tightly. She was dreaming. She would wake up, open her eyes, and find herself asleep in her own room. She would pick up her cell phone, type out a text message, make plans for later that evening. A movie, perhaps. Maybe flirting with guys whose bravado they would test with darting eyes and laughter. Anything but the endless sand and monotonous ocean. Anything.

Her jaw clenched, and roaring filled her ears. She would stop time, reverse it, travel back to fifteen when things between her and her mother were only difficult, not impossible. She would know better this time, know when to stop. She would not make the same mistakes.

I won’t, she promised. I won’t I won’t I won’t.

She opened her eyes. For just a moment, she’d believed herself capable of magic. Now, reminded of her inability to bend the world to her will, she succumbed to ordinary sullenness.

“Look,” her mother said. “A mall.”

Caddie, lured into looking out the window, saw only a faded Kmart sign rising from the expanse of a parking lot. Surrounding the store were others like it: Bed Bath & Beyond, Barnes & Noble, Jamba Juice.

“That’s not a mall,” she said scornfully. “That’s a shopping center.”

Her mother made no argument. Again Caddie thought of home, of the Beverly Center and its floors of shops. The withered Kmart passed from her view like one of the tired, washed-out hookers on the wrong end of Hollywood Boulevard. She imagined it filled with fat-assed women in too-tight sweatpants, dragging screaming children down the aisles as they searched for deodorants and cheap flip-flops. I might as well be in Van Nuys, she thought.

She wished she’d remembered to get some pot before leaving. Probably she could find some somewhere in Monterey; you could find pot anywhere, but she was almost certain it wouldn’t be any good. Probably just some shit grown by an old Deadhead in his backyard between the tomato plants and zucchini.

She didn’t even have her cell phone. Her mother had taken it away, fearing—rightly—that she would use it to phone Sam and Bree and hatch some sort of escape plan. Not that she couldn’t use any old phone, but the absence of her cell did make her feel adrift. It just seemed too much effort to actually dial, and she couldn’t remember the numbers anyway. Speed dial had reduced her memory for such things to nothing.

“Fuck,” she said loudly.

“Watch your mouth,” said Carol rotely.

“Whatever,” Caddie said, equally without enthusiasm. They were, both of them, too tired even for the most basic of skirmishes.

Carol turned the Lexus from the highway, exiting into Monterey. The scrubby pine trees and sand dunes were replaced by actual grass, and a town materialized seemingly out of nowhere. Caddie gazed at it hostilely, daring it to welcome her.

“It’s prettier than I remember,” Carol remarked. “Almost quaint.”

“Welcome to Mayberry,” said Caddie.

“It’s historic,” Carol said.

“It’s tired,” said Caddie. “Old and tired.”

“Like me,” Carol said before Caddie could. “You really need to get some new material, sweetie. I’ve heard this act before.”

Caddie retreated into silence and watched the town unfold before her. Small, boring houses. Sidewalks jammed with gift shops and used book stores and restaurants indistinguishable from one another. Nothing to entertain or entice her. Nothing surprising. Like her mother, she’d seen it all before, and she wasn’t impressed.

Kayak rentals. A Safeway. Signs for the famous aquarium her mother had tried to present to her as a reason for being excited about her enforced stay in Monterey. They passed in and out of her vision, forgotten in an instant, leaving behind a sour taste and mounting resentment.

“You could have just sent me to summer camp,” Caddie said.

“I could have,” agreed Carol. “But this way, you’ll have some time with your father.”

“He doesn’t even want me here,” Caddie said. “Does he?”

She looked at her mother, who didn’t answer immediately. “Of course he does,” she said after a moment.

“Now you’re the one who needs new material,” said Caddie. “Or at least acting lessons.”

“Look in my purse and see if the directions to your father’s house are in there,” Carol said.

Caddie unzipped the big leather bag and peered inside. It was filled with the odds and ends of her mother’s life—an address book, business cards from her real estate office, a lipstick. Caddie pawed through it. She found an orange prescription bottl

e. Valium. She tucked it into her hand. Beneath it was a piece of paper folded into quarters. She drew it out along with the pills.

“Here,” she said, holding out the paper while she tucked the Valium into the pocket of her sweatshirt.

“Read it,” said Carol. “I’m driving.”

Sighing, Caddie unfolded the paper. “Where are we?” she asked.

Carol looked for a sign. “Lighthouse,” she said. “It should be near the bottom of the directions.”

Caddie read. “Turn right on Clipper,” she said. “Lighthouse. Clipper. How goddamn nautical.”

“Just look for Clipper,” said Carol. “It should be right up here somewhere.”

“There,” Caddie said, pointing. “Just past that doughnut shop.”

Carol turned on her blinker, made the turn. They were heading uphill.

Caddie felt as if she were being walked to the gallows. She didn’t know why the idea of staying with her father was so unsettling, but it was. And it was more than just because she’d never spent more than a few days with him. Something about it felt like exile. She was removed from everything she knew, everything she enjoyed. Everything that made her her.

She felt like Dorothy, dropped into unfamiliar territory. Only no good witch would appear in prom drag to help her out. No clicking together of her heels would send her home. She was on her own.

She reached into the pocket of her sweatshirt and found the bottle. After deftly unscrewing the lid, she tipped the bottle until a single pill fell into her palm. A sip from the bottle of water she’d been nursing since their last stop for gas, and the pill slid down her throat. Work fast, she pleaded, waiting anxiously for the pharmaceutical security blanket to enfold her.

“Here we are,” Carol said, making another turn. “Look for number eighty-seven.”

Caddie didn’t want to look. She didn’t want to know which of the small, ugly houses was to be her prison for the next three months. She didn’t want to see the dull faces, like boiled potatoes, she was certain peered out at her from behind bleary windows. She felt as if she might be sick. With trembling fingers, she reached over and locked her door.

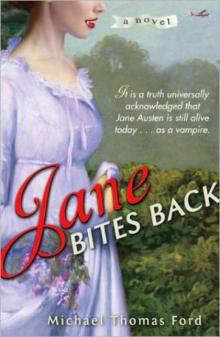

Jane Bites Back

Jane Bites Back Tangled Sheets

Tangled Sheets Z

Z Jane Goes Batty

Jane Goes Batty Lily

Lily Masters of Midnight: Erotic Tales of the Vampire

Masters of Midnight: Erotic Tales of the Vampire The Road Home

The Road Home Midnight Thirsts: Erotic Tales of the Vampire

Midnight Thirsts: Erotic Tales of the Vampire Suicide Notes

Suicide Notes Jane Goes Batty jb-2

Jane Goes Batty jb-2 Jane Vows Vengeance jb-3

Jane Vows Vengeance jb-3 Jane Fairfax 3 - Jane Vows Vengeance

Jane Fairfax 3 - Jane Vows Vengeance Michael Thomas Ford - Full Circle

Michael Thomas Ford - Full Circle Jane Bites Back jb-1

Jane Bites Back jb-1 Masters of Midnight

Masters of Midnight