- Home

- Michael Thomas Ford

The Road Home Page 2

The Road Home Read online

Page 2

“How do you know?” Burke argued.

“He doesn’t like you,” said Gregg.

Burke, surprised, looked at him.

“I’m sorry, sweetie, but he doesn’t. He thinks you’re overbearing.”

“I am not,” Burke objected.

Gregg gave him a small smile. “You kind of are,” he said. “Besides, I have to work. What about your insurance? Maybe they’ll pay for an in-home nurse. You might even get a hot one,” he added.

“My insurance doesn’t pay for anything,” said Burke. “I’ll be lucky if they cough up anything for this little vacation.”

“I can call them for you,” Gregg said. “We’ll find out.”

“I don’t want a nurse,” Burke complained. “The last thing I need is a stranger helping me to the toilet and trying to talk to me about his life while he’s giving me a sponge bath.”

Gregg didn’t come back with a smart response, which surprised Burke. It also worried him. Gregg’s sharp sense of humor waned only when he was trying to avoid confrontation. The fact that he wasn’t saying anything meant that he didn’t want to discuss the situation.

“Fine,” Burke said after a minute or two had gone by. “Call the insurance company. See what they’ll do. I’ll figure something out.” He waited for Gregg to nod in agreement, then added, “I’m tired. I think I should sleep now.”

Gregg got up. “I’ll let you know what they say. And you’re welcome.”

Burke didn’t look at him as he mumbled, “Thanks.”

“I’ll be back tonight,” said Gregg.

When Gregg was gone, Burke tried to form a plan. He hoped his insurance would come through, although he really doubted it. Having never been really sick, he’d always managed to get by with the bare minimum, figuring he would up his coverage when he got older.

Yeah, well, you are old now, he told himself.

He ran through a list of his friends, thinking about who might be able either to take him in or, better, to come live with him for a month or two, if he needed help for that long. He didn’t like the idea of having to move in with someone else. He liked being in his own place, even if he couldn’t get around it very well.

Gregg apparently was out as a potential nursemaid. But he had other friends. Oscar, maybe, or Dane. But Oscar worked long hours, and Dane was too much of a cock hound. Burke didn’t relish the idea of being in Dane’s guest room and listening to his host getting it on with one of his numerous tricks.

What about Tony? he wondered. Tony lived alone, and as a writer, he worked out of his house. But he has cats, Burke reminded himself. Just the thought of Tony’s three Himalayans—LaVerne, Maxine, and Patty—made his throat close up. No, his allergies would never survive an extended stay with the Andrews Sisters.

He continued mentally working his way through his address book. But for one reason or another, nobody fit the bill. Abe’s apartment was too small. Jesse was a slob. Ellen was a vegan. One by one he crossed the names off his list until he had run out of options. Then he rang for the nurse, asked for another shot of Demerol, and drifted into sleep.

When he awoke again, it was dark outside and his room smelled like his elementary school cafeteria. Gregg was once again seated in the chair by Burke’s bed. He indicated a tray on the table beside him.

“Salisbury steak,” he said. “And Tater Tots. Who’s a lucky boy?”

He picked the tray up and placed it on the movable tabletop that swung out from the wall beside Burke’s bed. Positioning the tabletop in front of Burke, he laid out the napkin and silverware as if he were setting a table.

“And what will you be drinking this evening, sir?” he asked.

“Gin and tonic,” said Burke. “Make it a double.”

“Water it is,” Gregg replied, pouring some from the plastic pitcher that sat on the table beside the bed.

Burke picked up the fork and poked at the meat on his plate. “When I was a kid, I always loved Wednesdays, because it was Salisbury steak day at school,” he told Gregg. “I was in college before I realized that it was just a fancy name for hamburger.”

“That explains your sophisticated palate,” Gregg joked. It was another difference between them—Gregg loved fine dining (Burke called it snob food), and Burke’s idea of cooking was opening a can of soup.

Burke was suddenly ravenous. He attacked his dinner with his good hand, managing despite the fact that he was a lefty and the utensils felt alien in his right hand. He wolfed down the Salisbury steak and Tater Tots. He even ate the green beans, which normally he would ignore. Only when he turned his attention to the small dish of chocolate pudding did he resume talking to Gregg.

“Did you talk to the insurance people?”

“I did,” Gregg answered. He cleared away Burke’s tray before continuing. “And you were right. They aren’t going to be particularly helpful.”

“Define ‘particularly,’” said Burke.

Gregg sat down. “They’ll pay only fifty dollars a day for in-home care,” he said.

Burke swore.

“And that’s after the five-thousand-dollar deductible,” Gregg informed him.

Burke’s response brought one of the nurses to his door. “Are you all right?” she asked, looking more than a little concerned.

“He’s fine,” Gregg assured her. “He’s having sticker shock.”

The nurse waited for Burke to confirm that he didn’t need anything, then left the men alone.

Gregg sighed. “So where does that leave us?” he asked. “I mean you. Where does that leave you?”

“I don’t know,” Burke told him. “You don’t want me, and I can’t think of anyone else.”

“It’s not that I don’t want you,” said Gregg. “It’s—”

“I know,” Burke interrupted. “I’m overbearing.”

“Just a tad,” said Gregg. “And I work. Don’t forget that. What about your other friends?”

“Sluts,” said Burke, waving a hand around. “Cats. Smokers. Don’t eat meat.”

“I see,” Gregg said. “Which brings us back to square one.”

“I have to pee,” said Burke.

“What?” Gregg asked.

“Pee,” Burke repeated. “I have to pee. Help me up.”

“Um, you’re not getting up,” Gregg said. “Remember?”

Burke glanced at his leg. “What am I supposed to do?” he said.

“This,” Gregg said. He held up a plastic container that he’d taken from a shelf beneath the bedside table. It resembled a water bottle on its side, with one end slightly angled up and ending in a wide mouth.

“You’ve got to be kidding,” Burke said.

“Come on,” said Gregg. “It’s not that hard.” He pulled back the blanket on Burke’s bed and started to lift Burke’s gown.

“Hey!” Burke said.

“Relax,” said Gregg. “It’s not like I haven’t seen it before.”

Burke relented, and Gregg hiked up the hospital gown, exposing Burke’s crotch. He placed the urine bottle between Burke’s legs.

“Ow,” Burke said. “Slow down.”

He tried to spread his legs, but when pain shot through the right one, he gave up and balanced the bottle on his thighs. Taking his penis in his right hand, he positioned the head at the mouth of the bottle and tried to pee. At first nothing happened. Then, as if a valve had been opened, urine spurted from his dick. Startled, he let go, and the bottle toppled sideways as he continued to pee. He attempted to grab at the bottle and hold on to his penis at the same time, but his left arm was useless, and he could accomplish only one of his goals. He clamped down, forcing the flow of urine to stop, but not before the hair on his legs was covered in drops of piss.

Gregg, who had prevented the bottle from falling to the floor, repositioned it. “Hold it,” he ordered Burke, who placed his right hand on the bottle. Gregg took Burke’s cock in his hand and inserted it into the bottle’s mouth.

“Don’t watch,” Burke said

.

Rolling his eyes, Gregg looked away. After a moment Burke was able to pee freely. He tried to ignore the fact that Gregg’s hand was holding his dick as he drained his bladder. He watched as the bottle filled up. For a moment he was afraid it might overflow, but then the stream slowed to a trickle. To his horror, Gregg milked the last few drops out before removing the bottle.

“Thanks,” Burke said.

Gregg took the bottle into the bathroom and poured it into the toilet. When he returned, he had a washcloth in his hand, which he used to wipe the spilled piss from Burke’s legs.

“I can do that,” Burke protested.

“Shut up,” said Gregg. “You don’t always have to be the big top, you know.”

Burke grunted. He wasn’t going to get into that particular argument with Gregg.

“There,” Gregg said as he put Burke’s gown back into place and pulled the sheet and blanket up. “Feel better?”

“No,” said Burke. He was already worrying about what he would do when he had to pee and Gregg wasn’t there. He certainly wasn’t going to ask any of the nurses for help.

“I had a thought,” Gregg said.

“About what?” asked Burke.

“About where you could stay.”

“Oh yeah?” Burke said hopefully. “Where?”

Gregg paused for a long moment. “With your father,” he said.

Burke laughed. “Right,” he said.

“I’m serious,” Gregg told him. “He has the room. He’s home all the time. It’s perfect.”

“Except that it’s my father,” said Burke.

Gregg looked him in the eyes. “You don’t have a lot of choices, Burke,” he said. “This is a good solution.”

“I’m not staying with my father for six weeks,” Burke said. “I’m not staying in Vermont.”

“There’s nothing wrong with Vermont,” Gregg argued. “It’s beautiful this time of year.”

“No,” Burke repeated. “End of discussion. I’d rather stay in this place than go there. I’ll think of something.”

“Okay,” Gregg said. “Just keep your options open.”

“Don’t try that on me,” said Burke.

“Try what?”

“That thing you do,” Burke said. “Whenever you wanted me to do something and I said no, you would tell me to keep my options open. That always meant you thought I would come around and do what you had wanted to do in the first place.”

“That’s not true,” Gregg said.

“No?” said Burke. “Have you forgotten about the vacation in Provincetown? The tile in my bathroom? The Volvo station wagon?”

“That Volvo saved your life,” Gregg said. “And I didn’t make you do any of those things. I just suggested.”

“Well, stop suggesting,” said Burke. “I’m not asking my father if I can stay with him.”

Gregg nodded. “All right,” he said. He looked at his watch. “I should go.” He leaned down and kissed Burke on the forehead. “Just think about it.”

“Get out,” Burke said, only half feigning irritation.

“Good night,” Gregg said as he left. “Don’t stay up too late. It’s a school night.”

CHAPTER 3

“Why didn’t you tell me there was only one road in Vermont?” Gregg asked as his Saab crested the top of a hill and descended into yet another green-grassed dell. On either side of the road black-and-white cows grazed lazily, only occasionally raising their heads to look at the passing car. “It really does look like a Ben & Jerry’s ice cream carton here, doesn’t it?” Gregg continued. “I keep expecting to see a Chubby Hubby tree.”

“Very funny,” Burke muttered. “Now you know why I never came back.”

“Stop it,” said Gregg. “It’s beautiful. And it’s just for the summer. Your mother and I will be back to pick you up in August.”

“You’re loving this, aren’t you?” Burke said.

Gregg grinned. “Maybe a little,” he admitted.

Burke shifted in his seat. His leg hurt like hell, and every time Gregg hit a rise or bump in the road, it sent another jolt of pain through the broken bone. “It would have been easier if the crash had just killed me,” he complained, attempting to shift into a more comfortable position and failing.

“Think of it as going to a sanatorium,” Gregg suggested. “Like one of those tragic tubercular women. Maybe you’ll meet some handsome man who was poisoned by mustard gas at Ypres and has been sent here for a rest cure.”

Burke stared at his friend. “You’re really not helping,” he said.

Gregg sighed deeply. “You’re determined to make this as miserable an experience as possible, aren’t you? I can tell. This is exactly how you were that time we took the house in Provincetown with Randy and Clifford.”

Burke groaned. “Heckle and Jeckle?” he said. “Those two talked nonstop from the time we picked them up until we dropped them off in Back Bay seven days later. It was all ‘When we saw Madonna at the White Party . . .’ and ‘Last season at the ballet . . .’ and ‘This cilantro is so good.’ Also, I have a broken leg and a broken arm.”

“Whatever,” Gregg said. “Are we almost there?”

“What was the last town we went through?”

“I believe it was Grover’s Corners,” Gregg said teasingly. “Or maybe Fraser,” he said truthfully when Burke gave him a vicious look.

“Then we’re about twenty miles away from Wellston,” Burke informed Gregg.

They rode the rest of the way mostly in silence. Burke looked out the window, dreading the moment when they would pull into the driveway of his father’s house. This was exactly how he’d felt returning to Vermont after his freshman and sophomore years at college—like he was being sent back to prison after a too-brief time on the outside. By the summer of his junior year, he’d found a job that allowed him to stay in Boston, and he hadn’t looked back. Apart from some Christmases during those first years following graduation and before he’d acquired his own circle of friends, he’d been back only a handful of times in twenty years.

“Wellston,” Gregg said as they passed the sign marking the edge of town. “Population three hundred forty-nine. Why, that’s practically a metropolis.” He leaned toward Burke. “I bet there’s even a Wal-Mart.”

Burke ignored him. He was watching the familiar landmarks of his youth appear outside the car window like the ghosts of school-yard bullies, each one greeting him with its own particular taunt. The Ebenezer Baptist Church (GOD CAN’T SAY THANKS FOR COMING IF YOU DON’T STOP BY!). The Eezy-Freezy (GET A HOT DOG AND A COLD CONE!). The Farmers Co-op (BARRED ROCK CHICKS $13.99 A DOZEN!). They all looked exactly as they had for decades, as if the entire town had been trapped in amber like a Cenozoic Era mosquito.

“Once we’re through town, turn left onto Crenshaw Road,” Burke told Gregg.

“He’s got his own road?” Gregg exclaimed.

Burke nodded. “When I was a kid, it was just RFD seventeen,” he said. “About ten years ago the county decided it needed a real name. Since my father’s place is the only one out here, they thought it would be funny to name it after him. It’s that dry Yankee humor you’ve no doubt heard so much about.”

They passed the Wellston General School (OUR GRADS ARE GREAT!), which marked the other side of town, and a quarter mile later turned onto Crenshaw Road. Narrow enough that the branches of the trees on either side created a kind of canopy overhead, and rutted enough that every few feet brought fresh curses from Burke’s mouth as his body was jarred by yet another bump, it wound lazily through a patch of woods before emerging into a long meadow. A post-and-wire fence separated the meadow from the road, and two chestnut horses peered over it hopefully, as if someone might at any moment toss them an apple.

The road curved to the right and became a driveway that led to a large white farmhouse. Daylilies, their orange and yellow heads bouncing lightly in the breeze, were planted in front of the screenedin porch that ran along the front of the house.

A beat-up red pickup truck was parked outside, and beside that stood a tall, somewhat heavy man with white hair, dressed in chinos and a red plaid flannel shirt. As the Saab approached, he lifted one hand to about chest level before returning it to his pocket.

“That means ‘hello’ in Vermontese,” Burke said. “It also means ‘You’re probably right about that snowstorm,’ ‘Them politicians is a bunch of fools,’ and ‘Sure I’ll have a piece of blueberry pie.’”

“He’s a good-looking man,” Gregg remarked as he pulled the car to a stop. “You don’t look anything like him.”

Burke rolled his window down. “Hi, Dad,” he said.

His father leaned in. “How was the drive?” he asked. “You hit traffic around St. Albans?”

“It was fine,” said Burke. “Could you help me out of here?”

His father opened the car door as Gregg got out and came around from the other side.

“Dad, this is Gregg,” Burke said as he turned sideways in his seat and swung his leg out.

“It’s a pleasure to meet you, Mr. Crenshaw,” said Gregg.

“Ed,” the man replied. When Gregg looked confused, he said, “Call me Ed. Everybody does.” He then squatted down, put Burke’s arm around his shoulder, and lifted his son up and out of the car.

“Do you want me to help you with that?” Gregg asked.

Ed shook his head. “He’s no heavier than a foal,” he said. “And he’s only got the two legs to contend with.”

As Ed helped Burke toward the house, Gregg opened the Saab’s trunk and removed the two bags he had packed under Burke’s exacting command. He followed the two men into the house, setting the bags down on the smooth, wide planks of the living room floor.

“Thought we’d put you in your old room,” Ed told his son.

“Upstairs?” Burke objected. “I can’t manage the stairs every time I need to come down here.”

“What do you have to come down for?” asked his father. “It’s not like you’re going to be feeding the horses or working in the garden.”

“What about meals?” said Burke.

“We got ourselves a Chinese restaurant in town now,” his father said. “Where the Tar-N-Feather was before Sandy accidentally set it on fire during his divorce from that California woman. It’s called Golden Pagoda, although as far as I can see, it’s not gold and there’s no pagoda. Run by a nice Japanese family. The father says he thought about sushi, but he didn’t think it would go over well in this part of the state. I suspect he’s right about that. Anyway, they deliver, so that takes care of that.”

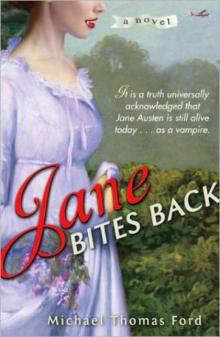

Jane Bites Back

Jane Bites Back Tangled Sheets

Tangled Sheets Z

Z Jane Goes Batty

Jane Goes Batty Lily

Lily Masters of Midnight: Erotic Tales of the Vampire

Masters of Midnight: Erotic Tales of the Vampire The Road Home

The Road Home Midnight Thirsts: Erotic Tales of the Vampire

Midnight Thirsts: Erotic Tales of the Vampire Suicide Notes

Suicide Notes Jane Goes Batty jb-2

Jane Goes Batty jb-2 Jane Vows Vengeance jb-3

Jane Vows Vengeance jb-3 Jane Fairfax 3 - Jane Vows Vengeance

Jane Fairfax 3 - Jane Vows Vengeance Michael Thomas Ford - Full Circle

Michael Thomas Ford - Full Circle Jane Bites Back jb-1

Jane Bites Back jb-1 Masters of Midnight

Masters of Midnight