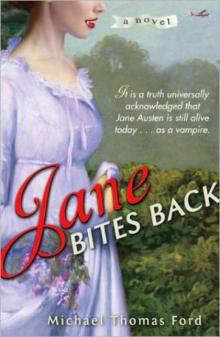

Jane Bites Back

Jane Bites Back Tangled Sheets

Tangled Sheets Z

Z Jane Goes Batty

Jane Goes Batty Lily

Lily Masters of Midnight: Erotic Tales of the Vampire

Masters of Midnight: Erotic Tales of the Vampire The Road Home

The Road Home Midnight Thirsts: Erotic Tales of the Vampire

Midnight Thirsts: Erotic Tales of the Vampire Suicide Notes

Suicide Notes Jane Goes Batty jb-2

Jane Goes Batty jb-2 Jane Vows Vengeance jb-3

Jane Vows Vengeance jb-3 Jane Fairfax 3 - Jane Vows Vengeance

Jane Fairfax 3 - Jane Vows Vengeance Michael Thomas Ford - Full Circle

Michael Thomas Ford - Full Circle Jane Bites Back jb-1

Jane Bites Back jb-1 Masters of Midnight

Masters of Midnight